Why The Right Is Winning

A simple, visual model for understanding conservative success and liberal failure.

I was thinking, as I often do, about how annoying right wing success is. Not how dangerous it is, or how sad it is, or how scary it is, just how annoying it is.

Supply-side economics has a pretty meager track record for lifting up all Americans, yet its tenets persist. And economic populism - the standard in most developed nations - falters in the homeland. What gives?

I was driving my family on a road trip last week, and, as has become their unfortunate custom, my wife and kids all fell asleep on me and left me alone with my thoughts. In that time, I set about devising a political model to explain as many things I could make it explain. It began to consume me. Such that I missed an important freeway exit and tacked almost a half hour extra onto my trip.

It’s not a bad habit for a writer/educator to try to find simple (if long-winded) explanations for complicated matters of high import. I doubt I’m the first to explore this territory. But I don’t know that I’ve ever seen it laid out in quite this way, so whatever, I’m planting my flag.

I humbly present to you: Dave’s Theory of Everything.

Enjoy.

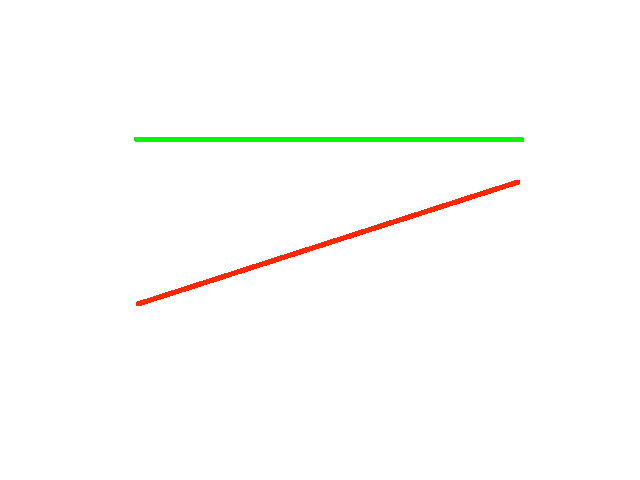

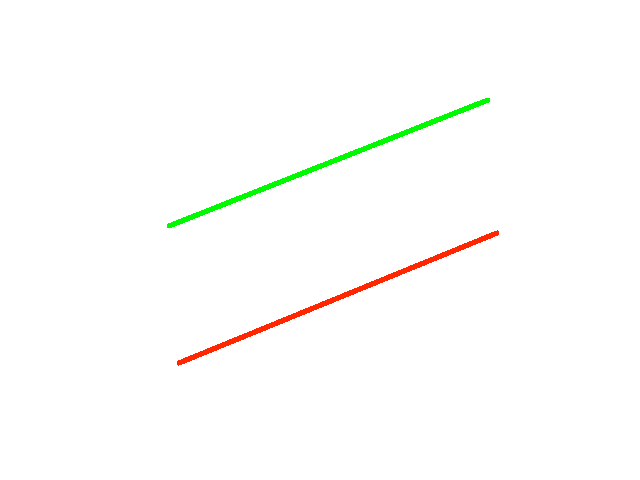

You start with this. Pretty much always.

This is an outcome gap. It might describe academic performance, personal health, quality of housing, tax burden, football teams, coolest X-man, really anything. All this model implies that most of the time, and in most use cases, things are not equal. Something is reliably going to be better than something else.

In political terms, this is the foundation for most domestic policy initiatives.

“We’ve noticed that some people have better healthcare than others.”

“We’ve noticed that some households pay more in taxes than others.”

“We’ve noticed that some cities have safer drinking water than others.”

It can be micro (some people have cancer), macro (some people are more likely to get cancer), left-coded (we should stop people from getting cancer), or right-coded (someone else getting cancer is not my problem).

Of course, we can flip it too; golf scores instead of hockey scores.

I’m not going to invert all of these as I trust my readers to extrapolate, but the above image would be your micro cancer gap: “some people have more cancer, others have less cancer, and it’s better to have less cancer.”

On the political left, the standard reaction to spotting a performance gap is to want to close it. This is actually true on the right also, but to a sometimes lesser extent. A conservative is less likely than a liberal to see a problem with some citizens having better access to healthcare than others, but the conservative probably does want individual cancer rates to be closer to that bottom line (no cancer). Likewise, a liberal sports fan would get bored very quickly if all baseball teams performed identically all the time.

You can’t perfectly map political preference onto this model, is my point.

Anyway, outcome gaps are stubborn things. Closing them - more commonly the purview of the left - is incredibly difficult.

Use Case: Education

I’m a teacher when I’m not doing this, and it was fellow Substacker,

, who turned me onto this line of thinking, and kind of broke my brain in the process.Put more simply and sadly, nothing in education works. Student outcomes are remarkably sticky even in the face of considerable intervention.

This perspective is both buttressed by a tremendous amount of evidence and yet considered impermissible in polite debate. And teachers and schools pay the price, as they are asked to control outcomes they have limited influence on.

What Freddie is talking about here is that the academic performance of students is highly stable. You have good students, you have bad students, and really no matter what you do, you’re always going to have good students and bad students. More than that, your good students are always going to be your good students, and your bad students are always going to be your bad students. The gap won’t close.

Here’s why:

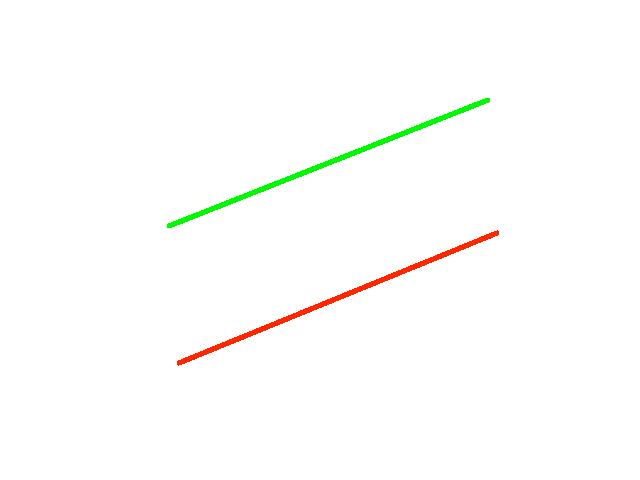

Say you’ve developed a crack new reading curriculum that massively boosts literacy rates. It works, it’s yours, and so you want to quickly start teaching it to all students. This is what happens:

See what we’ve done here? By sharing the curriculum with everyone, we’ve helped everyone equally. Literacy improved for all students, which is an unmitigated good, isn’t it?

Not so fast. Kids may be reading better but we have utterly failed to close the gap between our high performers and our low performers. Maybe we decide that’s not such a big deal. Maybe it’s not reasonable to expect all students to perform equally. Maybe we just live with the gap.

That’s easy enough when it’s a generalized performance gap. But what if we heat things up and make it a racialized one; white students are reading more competently than black students? (This is sadly true, by the way). You can quickly see how a left-minded policymaker would find this disparity intolerable.

So what to do?

Sticking with the literacy example for just another moment, we’ve established that simply offering the new curriculum, while helpful, doesn’t close the gap. This leaves us with three options.

Offer help unevenly:

We might do this by offering the curriculum only to the lowest performing students, perhaps in a special ed setting. It may seem problematic and unfair on the surface, but we do it all the time in education; math interventions, private tutoring, accommodations, etc.

Clip wings:

In this instance, we’re actively trying to lower the performance of our top students. This really is problematic and unfair. It’s also antithetical to the mission of education…which is not to say that we don’t sometimes do it. Deemphasizing or abandoning standardized tests is intended to engineer precisely this result. It does nothing for poor test-takers, just removes opportunities for the smarties to shine. That sucks, in my view. But for shot-callers who care more about gaps in outcome than overall outcome, it’s an appealing option.

Double whammy:

No reason we can’t do both. If we prop up the stragglers and smack down the high-fliers simultaneously, we’ll get that gap narrowed in no time. But the million dollar question: why the hell would we want to?

The Political Angle

This isn’t a piece about education, it’s a piece about politics. Applying this model to other public policy domains makes it very easy to see why policy efficacy is so untethered to popularity. Put differently, this will help us understand why even a lot of bad ideas are easy sells, while plenty of good ones are dead in the water.

Affirmative Action/DEI

Let’s start with a nice, spicy one; affirmative action. I have no empirical data to back up this claim, but the vibes tell me that however fierce opposition was to affirmative action in the 80s/90s/00s, it was nothing compared to the modern furor over “DEI.”

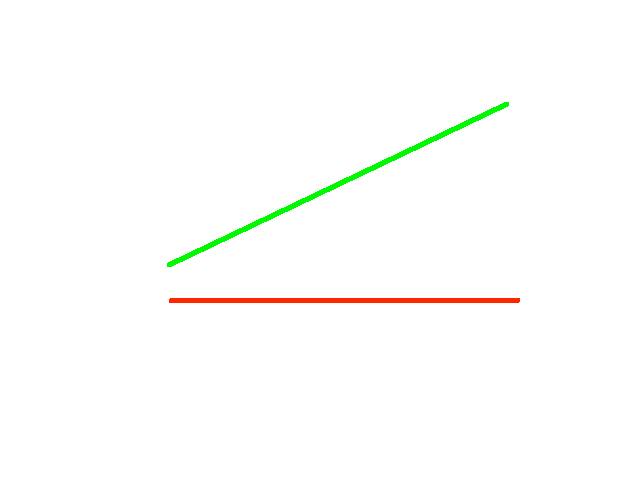

I think my model, plus a dollop of liberal naivety can explain this. Back in the day, affirmative action was *billed as* looking like this:

Conservatives never really bought this description, but I think liberals mostly did. The idea was that we could make diversity a value and elevate the formerly underrepresented without issuing too hard a screwing to folks at the top of the pyramid. Sure, maybe in an all-else-equal toss up, a white guy might lose out to an equally qualified black woman, but the black woman would still have to be sufficiently qualified.

Here’s Pete Buttigieg explaining DEI in these terms:

But as champions of affirmative action/DEI have become more strident in attempts to engineer their desired identity palettes, the game has been given away. Pretty clearly, what we’re looking at now is this:

Even a quick scroll of lefty social media now reveals that “diversity” isn’t really the true north anymore. Equally if not more exciting is the prospect of limiting options and spaces for white folks, men, (and most especially white men) in order to make way for people with more desirable skin pigmentations and anatomical equipment. This, as we’ll see, is a much harder sell.

Did the policy really change? Probably not. Or at least, not much. But the rhetoric sure did. The quiet part became the out-loud part, which helps explain the waning popularity of these initiatives, especially among the groups targeted for their righteous rogering.

The Poop Emoji Scale 💩

Obviously, my view of what an efficacious policy looks like will be different to a conservative’s. That’s okay. We don’t have to agree on what we want. But we might all benefit from being more introspective about how our ideas come across to those who don’t share them.

Politics is usually a game of trade-offs - an improvement here means a cost over there. Rarely in the modern era do we see unqualified goods. Even the observation that a sewer system is generally preferable to human waste flowing through the streets is not a free lunch situation (sorry for the imagery there). Sewers cost money and somebody has to put up that money.

To help quantify this, and to explore the political costs of various policy proposals, I’ve developed a scale. In keeping with our sewer example, and also because my sense of humor stopped evolving around the age of 11, I’ve decided to use poop emojis to help us visualize matters.

💩 - Minimal but nonzero political cost. Easy sell.

💩💩 - Some political cost but probably tolerable. A degree of grumbling expected.

💩💩💩 - Heavy political cost. Could change voting patterns.

💩💩💩💩 - Possibly fatal political cost. Hardest sell. Can topple parties.

Here’s what this looks like when expressed in terms of our outcome gap model:

💩 - Persistent Gap

This is a mostly good result. We’ve changed things universally for the better. The only problem is that we still have an outcome gap; things remain better for some than for others. (And one needn’t be a Marxist to take issue with this. If a new paradigm for policing improves the safety of all neighborhoods, but still leaves some neighborhoods safer than others, we’ve failed to reach full optimization. The goal is total safety with zero crime. Ergo, the gap - any gap - is unacceptable.)

💩💩 - Static For Me, Improvement For Thee

Here, we’ve helped the people or places in greatest need. But by failing to evenly distribute the aid, we can be credibly accused of behaving unfairly (“Why shouldn’t everyone have the nice, new thing?”). This is equity over equality.

💩💩💩 - Static For Thee, Decline For Me

Things have gotten materially worse for some, while remaining static for people better off. We should expect discontent from the losers at this. The only saving grace is that we haven’t robbed them and given the spoils to the winners exactly, we’ve just robbed them.

💩💩💩💩

Either trend results in 💩💩💩💩 , whether for the formerly advantaged group (left) or the for the already disadvantaged group (right). This is the proverbial slap in the face. Not only did you get screwed, somebody else directly made out at your expense.

On The Issues

By turning up the temperature on anti-white, anti-male rhetoric, liberals took affirmative action from a 💩💩 all the way up to a 💩💩💩💩. Nothing much changed about the concept itself, but in a spectacular feat of own foot-shooting, the left replaced deliberately inoffensive packaging with an inside-out garbage bag smeared with feces and old milk. Well done!

Rather frustratingly, the major political priorities of the American right tend to top out at the 💩💩💩 level. Most are below it. But the flightiest fancies of the American left often veer into 💩💩💩💩 territory. So before we even consider the merits, the left is playing with a graver handicap than is the right.

Conceiving of things in this way can offer us a political lens through which we might examine not just the cost of vying for a particular change but also the impact of the change once enacted.

Let’s look at some examples.

Easy Sells For The Left

Legal weed: 💩💩

Gay marriage: 💩💩

Civil/voting rights: 💩

Easy Sells For The Right

Deregulation: 💩💩

School choice: 💩💩

National security and military spending: 💩

Top Priorities - Right

These are some of the right’s top priorities, and also some of their least popular. But as we’ll see, none of them break three poop emojis on the scale. Conservatives have enjoyed significant success in these areas despite, in some cases, widespread popular opposition. We’ll see why that is.

Tax cuts for the wealthy: 💩💩

American income distribution takes the shape of a pyramid, with the very wealthy occupying the tiny, tippy top, and the poor filling the (very) fat base. Since offering relief to top earners necessarily means offering it to a numerically small group of people, one might expect these proposals to falter. They don’t though.

The favored explanation for this confusing dynamic is that the wealthy are better connected in government, so their wants and needs get more favorable hearings. This is certainly true, but it’s not the whole picture.

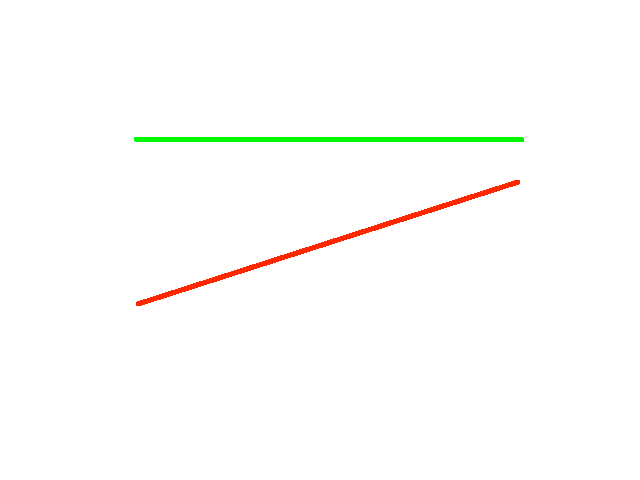

At least initially, the outcome gap for high income tax cuts looks like this:

It’s a two-poop emoji issue. Low and middle earners may not love the idea of high earners getting breaks they don’t need, but since there’s no immediate reduction in their life quality associated with these giveaways, they’re easy for political leaders to enact. This isn’t just why so many tax cuts are handed to the very wealthy, it’s why the cuts remain in place as persistently as they do.

Banning abortion: 💩💩💩

Democrats hoped the overturning of Roe v. Wade would be the political gift that kept on giving. They didn’t even really try to mitigate it, such was their conviction that the electoral gains they’d see would be so significant. They could get around to restoring a woman’s right to choose whenever they felt like it. It didn’t quite work out that way.

Abortion access didn’t materialize as the winner for the left, or the loser for the right, that the blue team anticipated. The reason, I submit, is that the issue took this form:

I used to have a bumper sticker in high school that read, “Against abortion? Don’t have one.” I thought it was pithy, and it remained on my car until some antagonist ripped it off while I was at choir practice. The thing is, the reverse of that sentiment works just as well: “Don’t need an abortion? Don’t need to get worked up when they’re banned.”

Spending cuts: 💩💩💩

The most consequential of spending cuts hit programs that aren’t relied upon by everyone. It’s another one of these:

Medicaid is a phenomenally important program for low-income Americans, just as Medicare and Social Security are phenomenally important to elderly ones. If you’re not in one of those groups, you don’t lose anything immediate when the integrity of those programs is threatened.

Now of course, the purpose of a social safety net is that it catches you when you need it to. Today, you might not. Tomorrow could be a different story. But that’s an abstraction to the slashers of these programs and to those who cheer them on. The political track to cutting is just smooth enough to allow it to happen, as we just saw with the Big Beautiful Bill.

Top Priorities - Left

Meanwhile, the juiciest targets for the left are all four-poop emoji catastrophes. Whatever their merits, they are enormously heavy lifts. This is true even of the ones that poll well (like single payer healthcare).

All three of the following issues conform to this variant of the outcome gap model:

Single payer: 💩💩💩💩

Paying for single payer healthcare would require a progressive tax increase; one hitting the wealthy harder than the less wealthy. Healthcare expenditures relative to income would decrease under single payer for a majority of Americans, who would save money by not having to pay premiums. But that still leaves a minority who’d see more money leaving their bank accounts every year to shoulder the tax burden.

There’s no point being glib about this (if for no other reason than glibness hasn’t worked). Many would see benefits to single payer, others would see losses. To those on the losing end, it’s salt in the wound that somebody else would be earning off of their perceived misfortune.

I am a staunch proponent of single payer. It might be my #1 priority - as in, I’d be comfortable retiring from political writing if it ever happened stateside. But the politics are an uphill climb, even with most Americans theoretically in favor, because you can’t easily beat the outcome gap problem. In the very immediate term, a lot of wealthy and powerful people would have to lose in order for their poorer and weaker neighbors to win.

Permissive immigration: 💩💩💩💩

This is a tricky one because it’s all perception. The right regards mass immigration as a net negative in terms of their quality of life: more immigrants = more change = more tearing at the cultural and economic fabric of the country. I don’t share this view, but my sensibilities are irrelevant to the model. The left wants to help immigrants, the right regards that as being to their detriment, so we find ourselves in another four-poop emoji situation whether we think that’s fair or not.

Trans rights: 💩💩💩💩

Whether you don’t want biological males in women’s sports, or bathrooms, or prisons, or whether you just don’t like all this pronoun business, the left has framed the fight over trans rights in terms that pit trans gains against losses for skeptics. I think that was a total own-goal, and utterly pointless in civil rights terms. But I wasn’t consulted or listened to.

True civil rights aren’t zero sum - we all get them. But trans rights activists went out of their way to choose hills to die on that are zero sum. If your prerogative is reserving access to women’s spaces for biological females, and I force the inclusion of trans women in those spaces, one of us has to lose. We can’t both have our way. The bitter hatred on both sides of this debate is a byproduct of this give-and-take. If I win, you lose, and if you win, I lose. One comes at the expense of the other. So these issues - issues that effect a tiny fraction of the American population - loom large in the public discourse by virtue of their being four-poop emoji gambits.

Conclusions

Obviously, the priorities of left and right are unlikely to change because *Dave drew some lines* but since having this epiphany, I’ve struggled to get it out of my head. I’ve found myself conceiving, almost obsessively, of matters large and small by picturing lines in space, who and what they represent, and the directions in which they might be traveling.

If nothing else, this could help liberals better tailor their policy ideas for mass consumption, and maybe avoid affirmative action-like pitfalls. Environmentalism, for instance, is a 💩 when we’re talking about renewables and efficiency, but climbs to a 💩💩💩 when we’re telling people to ditch their air conditioners and SUVs. Of course, this will fall on deaf ears with the subset of the left that gets off on scolding and hectoring, but the utilitarians may find some value here.

I don’t claim to have uncovered anything revelatory in this. I intend it merely as a visualization of the political costs attendant to closing outcome gaps. But since we do that a lot, especially on the left, it might be good to have a way of considering our work that prepares us for the level of resistance it might meet.

Let me know in the comments if you can think of other uses for this. And especially, let me know if you can think of exceptions, or areas where the model doesn’t work.

Seems fair. Here in Seattle, the school board once had the goal of eliminating the race gap in performance within 5 years. (They didn’t.) Now their latest stratagem is to eliminate gifted-student programming. If they don’t know how to get Black kids to do better in school, they can at least bring the white and Asian kids down a notch. Then they had to hire a consulting firm to help them explore why parents have been pulling their kids out of the public schools.

Good piece. Enjoyed it.

I think Deregulation is a both-lines-moving-up issue - no poop emoji.

the poor can't be housed on the left coast and housing costs are out of control because REGULATION prevents anything from being built.

Left-coast was a typo - but so accurate that i'm leaving it in.